contributed by Michael Ferron, Easterseals Crossroads Board Member

In 1921, a white supremacist mob violently attacked the Greenwood District in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Greenwood—popularly called Black Wall Street—was a prosperous community replete with Black business owners, restaurateurs, lawyers, doctors, and other professionals.

The Tulsa Race Massacre left ten thousand people homeless, eight hundred injured, and at least three dozen dead—though many researchers estimate the death toll to be as high as three thousand. Additionally, the two-day race riot decimated decades of Black socioeconomic progress. It destroyed more than thirty city blocks in the Greenwood community, including more than two million dollars (approximately $33 million in 2020 dollars) in property damage.

John (The Baptist) Stradford

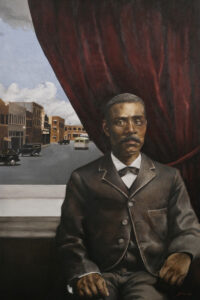

Among the wreckage and ruin was the Stradford Hotel, one of several Greenwood hotels J. B. Stradford and his wife Bertie Eleanor Wiley Stradford owned. At the time, Mr. Stradford was one of the wealthiest and most prominent Black entrepreneurs in the United States. He graduated from the Indianapolis College of Law, a predecessor to the Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law in Indianapolis. Mr. Stradford practiced law here and opened his first hotel in Alexandria, Indiana, in 1899. Later that year, he and his wife moved to Tulsa and began developing hotels and real estate. (portrait of JB Stadford at right by Jay Parnell).

Among the wreckage and ruin was the Stradford Hotel, one of several Greenwood hotels J. B. Stradford and his wife Bertie Eleanor Wiley Stradford owned. At the time, Mr. Stradford was one of the wealthiest and most prominent Black entrepreneurs in the United States. He graduated from the Indianapolis College of Law, a predecessor to the Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law in Indianapolis. Mr. Stradford practiced law here and opened his first hotel in Alexandria, Indiana, in 1899. Later that year, he and his wife moved to Tulsa and began developing hotels and real estate. (portrait of JB Stadford at right by Jay Parnell).

The Stadfords purchased large tracts of land, developed them, and sold some of the properties exclusively to Black people for housing and the opportunity to start their own businesses. They believed that combining resources would give other Black people the same economic opportunities as white people. This ethos inspired other Black business owners to do the same and created immeasurable wealth during a period of pervasive racial segregation and discrimination.

During his first two decades in Tulsa, Mr. Stradford became a prolific business magnate: his home was worth $125,000 ($1.95M in 2020 dollars), and he owned two dozen rental houses, a 16-room brick apartment building, pool halls, shoeshine parlors, and spas. By the mid-1910s, Mr. Stradford earned over $8,500 (2020) per month in revenue. Then, in 1918, he purchased the crown jewel of his real estate portfolio at 301 North Greenwood Avenue.

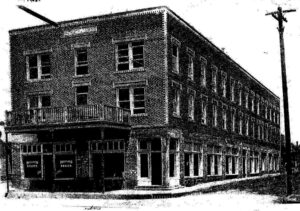

The Stradford Hotel

The Stradford Hotel

Mr. Stradford founded his namesake hotel to give Black Tulsans access to the same amenities as segregated hotels. “The Stradford would be a monument to the thrift, energy, and business tact of the race in Tulsa [and] to the race in the state of Oklahoma,” he remarked during the hotel’s grand opening. At the time, the Stradford Hotel was the largest Black-owned and operated hotel in the country. It had 54 rooms, a casino, pool hall, bar, and restaurant. Along with the Commodore Cotton Club across the street, the hotel filled Greenwood Avenue with jazz music, giving Black residents the freedom to dance and commune without fear.

Civil Rights Activist

In addition to his business acumen, Mr. Stradford was a fervent advocate for racial and economic equality and a follower of W. E. B. Dubois, co-founder of the NAACP. He sponsored Mr. Dubois’s March 1921 visit to Tulsa as part of Dubois’s nationwide book tour.

Mr. Stradford’s activism included refusing to move to the back of a segregated train car resulting in his expulsion—he would later sue the rail company for discriminating against Black riders. He also fought against police brutality and corruption, championed women’s reproductive rights, and used his legal training to represent numerous Black men who would have faced certain death whether convicted or not. Moreover, Mr. Stradford often organized large groups to protest the lynchings of Black people.

On several occasions, Mr. Stradford’s army of protesters outnumbered the lynch mob saving many Black Tulsans from a horrific death. He collaborated with the editor of the Tulsa Star to write articles about his advocacy, including one entitled “Near Lynch Victim Proved to be an Innocent Man.” Following back-to-back lynchings and the arrest of a Black man—who surely would have been lynched—after winning a bar fight against a white man, Mr. Stradford became even more passionate about police accountability and the scourge of racial violence.

When the City of Tulsa enacted a law mandating housing segregation, Mr. Stradford unsuccessfully lobbied the mayor to veto it and Tulsa’s district attorney to condemn it to the ire of local segregationists. The Oklahoma Supreme Court later invalidated the ordinance, and the United States Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional. But the law remained on the books until the 1960s with police enforcement. Some historians believe Mr. Stradford’s remonstration precipitated the deadly attack a few years later.

“The single worst incident of racial violence in American history.”

On May 31, 1921, police arrested a young Black man who became at risk of being lynched by a white mob. Mr. Stradford had no confidence that the police chief would protect the young man, so he a group and went to the courthouse. Violence broke out, and Mr. Stradford fled to his hotel to protect it. Machine gun fire destroyed the hotel’s windows and façade, and Mr. Stradford fought to fend off the rabid crowd throughout the night. Eventually, the National Guard arrived and attempted to evacuate the Greenwood District. However, Mr. Stradford and other hotel owners refused to abandon their property. The National Guard promised them that their properties would not sustain further damage if they surrendered.

Mr. Stradford and the others sheltering at the Stradford Hotel agreed, but the National Guard confiscated all the money in his hotel and burned it to the ground. A few days later, Mr. Stradford was the first person charged with inciting a riot, for which the penalty was life in prison or death. Well aware of his fate, Mr. Stradford gathered his remaining cash and escaped on a train to his brother’s home in Independence, Kansas.

Shortly after his arrival, the local police showed up at Mr. Stradford’s brother’s house. They asked him to turn himself in, to which Mr. Stradford replied, “Hell no!” Nevertheless, police arrested and booked him in the local jail. While out on bail, the police told Mr. Stradford to appear for court about a week later. Instead, Mr. Stradford and his son Cornelius Francis Stradford, also an attorney, fled to Chicago. He fought extradition to Tulsa and settled in the Windy City, where he remained branded a fugitive from justice for the rest of his life.

Resilience and Remembrance

Mr. Stradford was born into a formerly enslaved family in Kentucky on September 10, 1861. After a lifetime of building the kind of wealth and social status that Black people in that era could only dream of, Mr. Stradford lost everything during those two days in Tulsa. Like all the other Black property owners in Greenwood, insurance companies refused to pay any claims. In the end, Mr. Stradford lost his hard-earned fortune and reputation.

Always a shrewd businessman, Mr. Stradford rebuilt his life and started new businesses in Chicago. While he never regained his former affluence, Mr. Stradford opened a candy store, barbershop, and a small pool hall. His descendants said the injustice Mr. Stradford endured during the Tulsa Massacre always affected him. Mr. Stradford died in Chicago on December 22, 1935.

In 1996, with the help of an Oklahoma legislator, Mr. Stradford’s great-grandson fought to clear his name. The Tulsa district attorney re-examined the case, determined that Mr. Stradford and several other Black were wrongly charged with rioting, and exonerated all of them 75 years after the infamous bloodbath.

Last year, the I.U. McKinney School of Law held a ceremony to honor Mr. Stradford’s legacy. His family members attended the event, where the law school unveiled a portrait of Mr. Stradford that commissioned Indianapolis artist Jay Parnell to paint. Students and visitors can see the portrait on display on the second floor of the law school.

—

Michael Ferron joined the Easterseals Crossroads board of directors in 2016 and has served as ESC’s development committee chair for the past three years. In addition to being a disability advocate, Mr. Ferron is a real estate broker and instructor. His professional and research interests focus on the intersection of race, housing, and poverty. In May 2022, Mr. Ferron will earn a law degree and graduate certificate in civil and human rights law from the Indiana University McKinney School of Law—Mr. Stradford’s alma mater.